The story could not start off any worse. Famine in Judah has forced a small Hebrew family to flee their beloved homeland and find refuge in Moab. Yes, Moab. Elimelech, Naomi, and their sons, Mahlon and Chilion, are forced to shift residency and dwell among a foreign people.

It would be easy for us, as readers far removed from the foreign relations of ancient Israel, to skip over this detail and miss the intensity and offense that launches this biblical narrative into its subversive plot. But a Jewish reader or hearer living in antiquity would certainly not miss the punch that has been thrown.

The Moabites are enemies to Israel. They are dreaded dwellers in the region just opposite of Judah and across the Dead Sea. They are a people whose biblical ancestry stems from the incestual relations Lot had with his daughters (Gen. 19:30-38). The Moabites have not once demonstrated compassion or neighborly love towards God's covenanted people, actually their king sent Balaam to curse the numerous people who had "come out of Egypt" (Num. 22). They are ultimately remembered for leading Israelites into Baal worship through the seduction of a few of their women (Num. 25:1-3). They are then forever shunned and forbidden from the worshipping community and assembly of the pilgrimaging Israelites (Deut. 23:3-6; Nehemiah 13:1-3). That said, the writer of Deuteronomy incorporates among the miscelaneous laws for the nomadic Hebrews:

Yet this is precisely where this family from Judah now calls home. Their welfare is wrapped up in the welfare of Moab. But it gets worse, especially for Naomi."You shall never promote their welfare or their prosperity as long as you live" (23:6).

Elimelech dies.

Naomi's sons marry two Moabite women, Ruth and Orpah. (I will spare you the Oprah jokes)Here we go again, says the ancient hearer. Faithful Israelites to be led astray by Moabites.

Yet, before cynicism can really take root in the opening preface, the sons also meet their death.

Naomi now left alone. A childless widow in Moab. Shalom nowhere to be found.

The widowed Hebrew, whose name means "sweetness," knows only bitterness. So she changes her name to reflect her circumstance, even her relationship with Yahweh. She is now Mara, "the bitter one."

But not before her bitterness is met with surprising remarks from her daughter-in-law, who shares similar grief as she also mourns the loss of a husband:

While Orpah has heeded the advise of her mother-in-law and returned to Moab, Ruth insists on fidelity. She surrenders everything familiar and pledges a new kind of allegiance to Naomi and Naomi's God, whose name is Yahweh. This is particulalry poignant when the reader recollects that this story comes on the heels of the heinous infidelity of Israel's judges."Do not press me to leave you or turn back from following you! Where you go, I will go; where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God" (1:16).

In short, this is not your grandfather's Moabite. She is quite different.

Coupled with Naomi, they return to Judah and work the system in search of redemption.

Ruth gleans from the fields of the prominnent landowner, Boaz, who also happens to be the relative of Naomi. When he learns of the status of this young woman, i.e. a Moabite, instead of adhering to Deuteronomical law and shunning the foreigner, he extends radical compassion and generosity. When Ruth inquires of the gracious provision, Boaz replies:

So much for the exclusion of the Moabites. Instead, Ruth has found refuge, redemption, welfare, and shalom in the assembly of the LORD. Boaz and Ruth undo the racial and ethnic segregation of the law."All that you have done for your mother-in-law since the death of your husband has been fully told to me, and how you left your father and mother and your native land and came to a people that you did not know before. May the LORD reward you for your deeds, and may you have a full reward from the LORD, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come refuge!" (2:11-12)

But Ruth and Naomi would not stop there. They press on and continue their quest to push the marginalized to the center and draw the privileged and powerful to the marginalized.[1] Bread, grain, and sheaves were one thing, everlasting deliverance from the bitterness that has become their entire lives was another.

Ruth, as advised by Naomi, approaches Boaz at the threshing floor at midnight, dressed in her finest, and uncovers the feet of her next-of-kin. You don't need to stretch your imagination to hear echoes of the ancient euphemism. Yet, unlike the seduction of her ancestors that led to the idolatry of Israel, this one is a move towards fidelity on behalf of a Hebrew widow.

And it works. She requests the betrothal of her next-of-kin, which in turn would lead to the ultimate redemption of Ruth and Naomi.

And the whole world, too. Boaz would oblige, embrace Ruth as his bride, and the two would conceive a child. His name was Obed, yet-to-be father of Jesse, and grandfather of King David.

As Naomi, the bitter grandmother, presses her grandson against her chest, one could only imagine what images scrolled through her mind. In her anguish and sorrow, did she ever imagine that Yahweh would ever deliver? As she fled famine, mourned the loss of husband and sons, did she ever dream that her rescue would come through a Moabite? When she did return home, would she have ever guessed that her plight would be resurrected into welfare not only for her and Ruth, but also for all of Israel and the whole world.

There is no way that even the birth of a baby can overshadow and undo the suffering experienced by this Hebrew woman and her companion, Ruth. It would be foolish to think that in Naomi's joy there were not also tears of lament, wishing her deceased husband were there to witness the birth of this child. Surely she could not have helped but desire Obed to be the fruit of her actual son, so he would truly share the bloodline."...and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of of Jesse, and Jesse the father of King David...and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah" (Matthew 1:5, 16).

But surely she would never have expected that the same Yahweh, whom she knew only as one who brought harsh calamity upon her, through her would also deliver the Messiah.

I guess you can say the story could not have ended any better...

Questions to Ponder:

What are some of the intolerable life experiences that have made it difficult to see God and God's promises as true and good? (Naomi)

Who are some of the people, maybe unexpected, that have journeyed alongside us and quested to move us towards healing and hope? (Ruth)

Who are people and groups of people we may often isolate, ignore, or hold to offensive stereotypes? How have we struggled to see them as valid members of the people of God? Have we been victims of the same treatment? (Moabites)

How has the Bible been used to exclude and offend marginalized neighbors? What do we do when we discover that maybe God is doing something new in those often relegated to the fringe of society and church alike? What about when our biblical interpretations and positions are challenged to change? (Moabites as viewed through Pentateuch versus Ruth)

What would it look like for us to work towards reconciliation and welfare of those typically reduced to the margins with those often situated in positions of privilege and power? Have you had any experiences when this has happened? (Ruth/Boaz)

How can we quest to hear and retell the stories of those whose voices are often silenced and left unheard? (Book of Ruth) [2]

Notes:

[1] See article: "A Theology of Ruth: The Dialectic Tension or Countertestimony and Core Testimony" by Nathan Tiessen (Direction 2010)

[2] "These books [Ezra and Nehemiah and all of pentateuch] show very clearly that foreign women are a danger to post-exhilic Judahite society and therefore have to be rejected. Ruth, on the contrary, is not rejected. Her story is told to convince the reader that a Moabite woman is not dangerous at all, but can be a valuable member of Judahite society. Thus, the book of Ruth is an answer to Ezra's and Nehemiah's politics of demarcation against foreigners and their interpretation of Deuteronomy. As a result, Israelite identity is not endangered by a Moabite like Ruth" ("Foreigness and Poverty in the Book of Ruth" by Agnethe Siquans in Journal of Biblical Literature, 2009. p. 449).

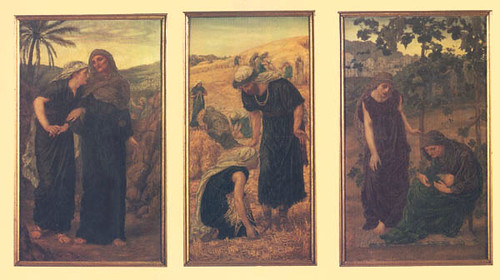

[3] the image above is featured on: http://www.bib-arch.org/online-exclusives/ruth-2.asp